Irina Alexandrovna Zborovskaya – doctor of medical sciences, professor,cathedral professor of hospital therapy with the course of clinical rheumatology of the doctors improvement faculty of Volgograd state medical university, director of the Federal Budgetary State Institution (FBSI) “Research and development institute of clinical and experimental rheumatology” of the RAMS, head of the regional Osteoporosis Center, presidium member of the Association of rheumatologists of Russia, member of the editorial boards of the magazines “Scientific and practical rheumatology” and “Modern rheumatology”

Definition. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disorder which is pathogenetically associated with increased production of a variety of organic nonspecific autoantibodies to different components of the nucleus as well as increased production of immune complexes. SLE involves inflammation (that is the immune system’s response to kill foreign agents, virus, bacteria) that can affect almost any organ or tissue and lead to multiple organ failure depending on disease activity.

Epidemiology. The incidence of SLE averages 15 to 50 cases per 100,000 population. Females of childbearing age are 8 to 10 times more frequently have SLE than males. Families of patients with SLE have a higher disease incidence. Moderately high concordance rate (about 50%) of SLE is observed among monozygotic twins. Worldwide, different races and ethnic groups appear to have varying rates of disease. The higher prevalence of SLE is among black women and men. However, it is less common among Hispanics and Asian populations and exceedingly rare among white women and men.

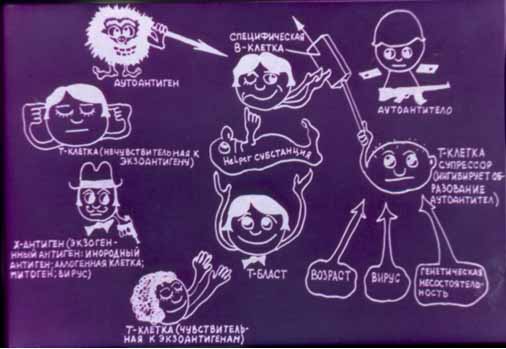

Aetiology. Although the specific cause of SLE is unknown, multiple factors are associated with the development of the disease. These include genetic peculiarities of immune response, hormonal, and environmental factors.

Genetic factors. SLE occurs most commonly in families with deficiencies of complement. Some human leukocyte antigens HLA-DR2, HLA-DR3, HLA-B8 occur more often in people with SLE than in the general population.

Photosensitivity. Ultraviolet irradiation (most commonly UV-B, less commonly UV-A) stimulates apoptosis of skin cells. It usually results in the formation of intracellular autoantigens located at the membranes of the involved cells and in the development of an autoimmune process in genetically predisposed people.

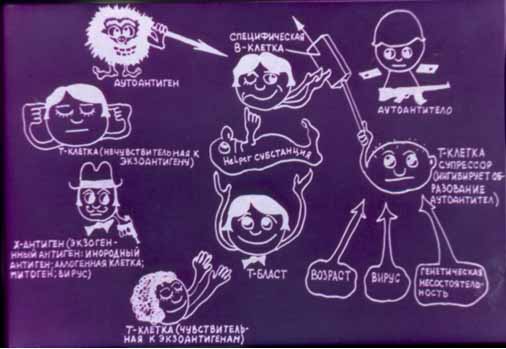

Evidence for the role of viral infections in SLE is controversial. There is evidence for the role of viruses of measles and measles-like viruses in the onset of the disease. RNA cells appear to have viruses that can play a significant role in SLE. Molecular mimicry of virus proteins and lupus autoantigens (for example, Sm) is common in SLE. Serologic characteristics of being infected with Epstein-Barr virus are most commonly observed in patients with SLE than in the general population.

Hormonal factors. Sex hormones contribute to the formation of immunologic tolerance and play an important role in SLE. Women of childbearing age have SLE 7 to 9 times more frequently than men. However, pre- and postmenopausal women have SLE only 3 times more frequently than men.Reduced testosterone level and increased secretion of estradiol is typically observed in men with SLE.

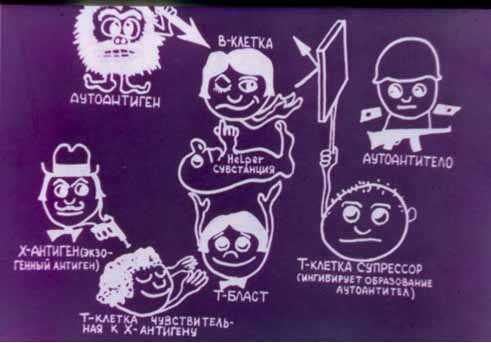

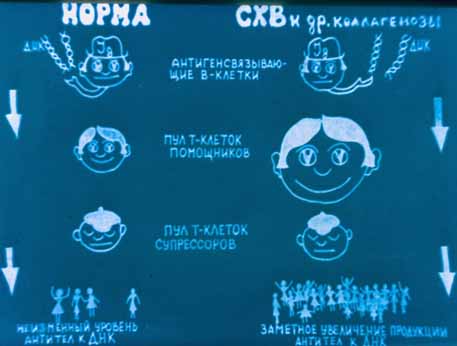

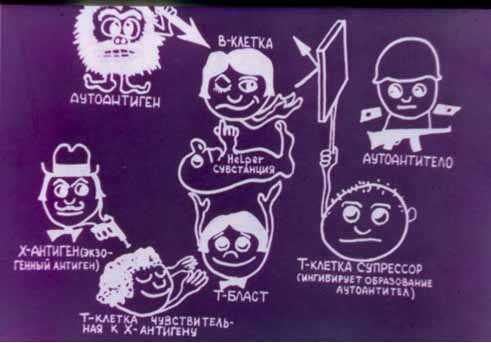

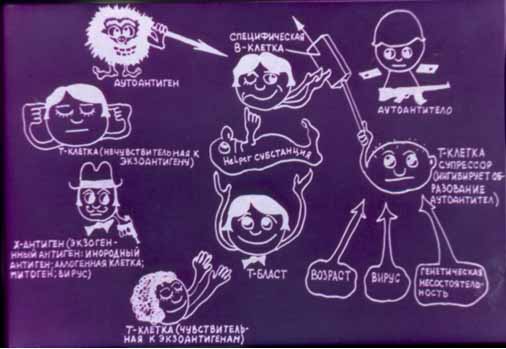

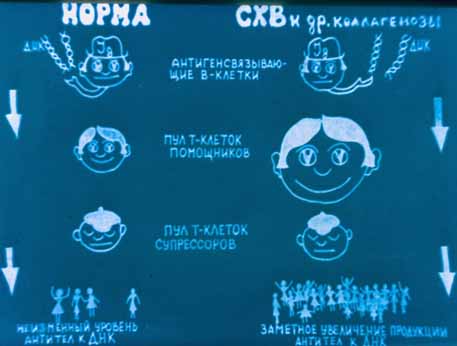

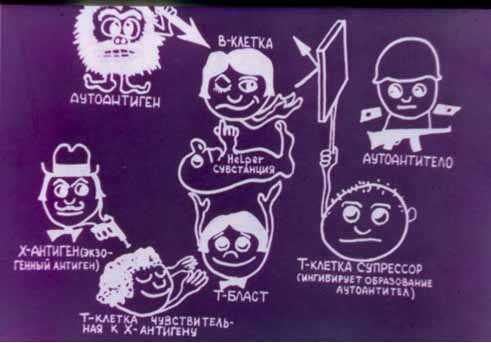

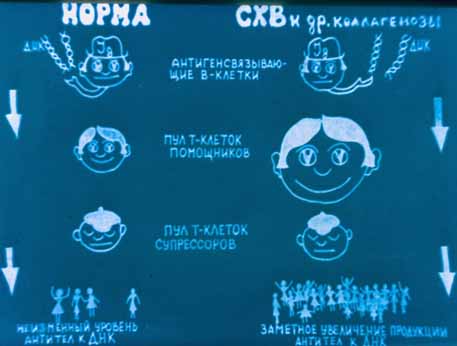

Pathogenesis. At the early stage of SLE polyclonal (B-cell) activation of immunity occurs. It is typically alternated with antigen – specific (T-cell) activation of immunity. Disturbances occurring in the immune system in SLE include congenital or induced defects in apoptosis with increased cell death.

In patients with active SLE autoantibodies develop only to 40 (although there are more than 2000) potentially autoantigenic cell components, the most important being DNA and intracellular nucleoprotein complexes (for example, nucleosome, ribonucleoproteins, Ro/La, etc.).

High immunogenicity of autoantigenic cell components is associated with their capability to cross-react and bind B-cell receptors and accumulate on cell surfaces. Various defects of cell immunity are common in SLE and are usually characterized by increased production of Th2-cytokines (IL-6, IL-4 and IL-10). The latter are considered to be autocrine factors of B-lymphocyte activation synthesizing antinuclear antibodies. However, estrogens are capable of stimulating synthesis of Th2-cytokines.

Disturbances in the immune system occurring in SLE lead to the production of autoantibodies and immune complexes. T-lymphocytes also play an important role in the development of the disease. A high ratio of CD4 to CD8 T cells as well as some other T cells stimulate production of autoantibodies. Activation of autoreactive B- and T-lymphocytes in SLE is caused by many factors. They include defects in immune cell tolerance, apoptosis, production of anti-idiotypic antibodies, formation of immune complexes and proliferation of cells which control the immune response. These antibodies target cells leading to cell damage and their impaired function. Damaging action of some autoantibodies is accounted for by their link with some antigens, for example, with superficial erythrocyte or platelet antigens. Other autoantibodies can bind with several antigens. Antigen-antibody complexes can activate the complement leading to tissue involvement. Along with this, the presence of antibodies on cell membranes can lead to impaired functions of cells even when the complement is not activated.

Circulatory immune complexes and autoantibodies usually cause tissue involvement and impairement of functions of various organs. Skin, mucous membranes, central nervous system, kidneys and blood are most commonly involved in SLE.

Although pathogenesis of lupus nephritis is unknown, the following mechanisms are considered to be responsible for the onset of the disease: deposition of circulatory immune complexes; local formation of immune complexes; crossed interaction of antibodies to DNA with glomerule components.

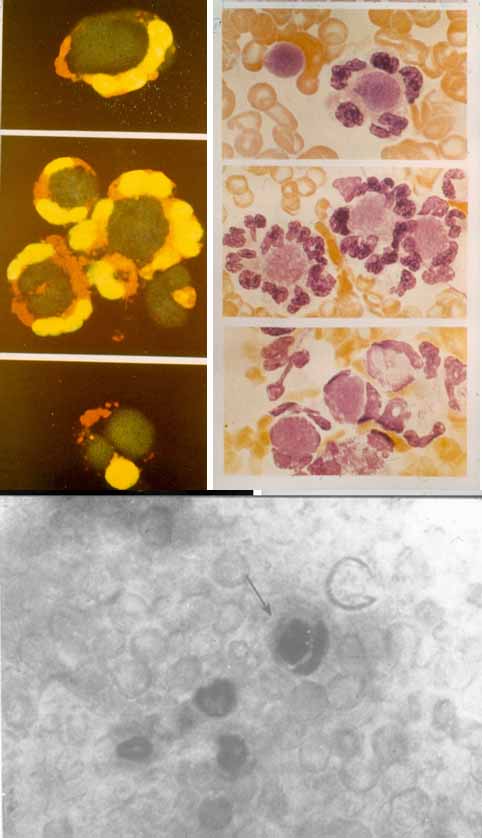

Morphological changes. The most common microscopic changes are the following:

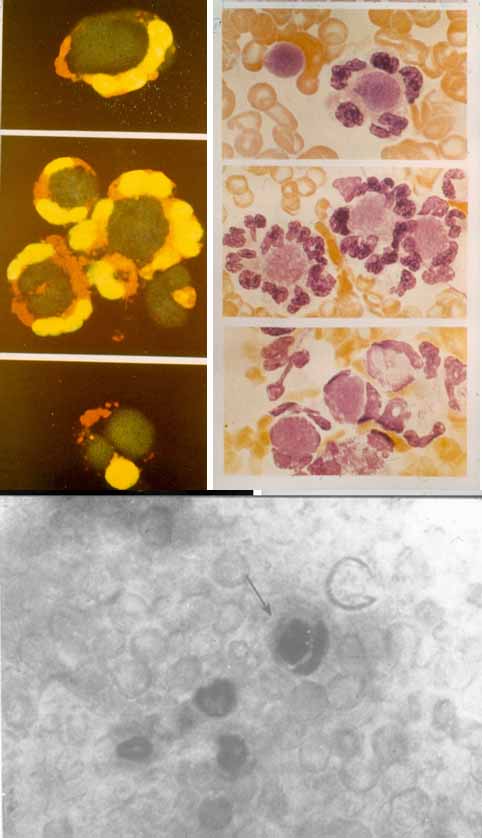

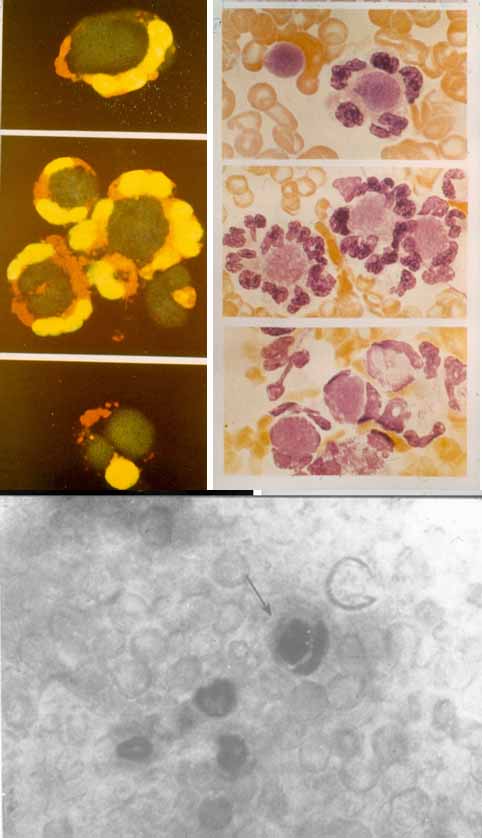

- Hematoxylin bodies. Amorphous masses of the nuclear substance stained purple-blue by hematoxylin are detected in the loci. Neutrophils which absorb the corpuscles in vitro, are called LE-cells.

- Fibrinoid necrosis. Immune complexes in the connective tissue and in vascular walls which consist of DNA, antibodies to DNA and of the complement present a picture of fibrinoid necrosis.

- Sclerosis in the vessels of the spleen. “Onion skin” phenomenon can occur in patients with SLE. It is typically associated with perivascular concentric deposition of collagen.

Changes in tissues

Cutaneous manifestations of SLE: Immunoglobulin (Ig) and complement are deposited in skin resulting in necrosis of tissue at the dermoepidermal junction. Peculiar discoid lesions have follicular plugging with hyperkeratosis and atrophy of the epidermis. Open injuries of the walls of small vessels in the skin (for example, leucoplastic vasculitis) can also be a feature of SLE.

Renal involvement. Immunocomplex glomerulonephritis is a common manifestation of SLE. Mesangial nephritis occurs as a result of deposition of Ig in the mesangium. It is considered to be the most frequently occurring lesion in SLE. Focal proliferative nephritis is characterised by the involvement of glomerule segments (usually less than 50% of glomerules). However, the disease can progress resulting in diffuse involvement of glomerules. Diffuse proliferative nephritis is characterised by cell proliferation of a great amount of glomerule segments in more than 50% of glomerules. Membranous nephritis usually occurs as a result of deposition of Ig in the epithelium and peripheral capillary loops. In membranous nephritis proliferation of glomerule cells does not occur. Membranous nephritis occurs rarely, however, some patients may present with a combination of proliferative and membranous changes. Membranous nephritis is a better prognostic marker than proliferative one.

Interstitial inflammation can be observed in all above mentioned cases. Necrosis of glomerules, epithelial demilunes, hyaline thrombus, interstitial infiltration and necrotic vasculitis are common features of acute glomerulonephritis picture. These changes are fully reversible. However, glomerulosclerosis, fibrous demilunes, interstitial fibrosis and atrophy of canaliculi are considered to be irreversible histologic findings (Table №1).

Central nervous system involvement. Perivascular inflammatory changes of small vessels, microinfarctions and microhemorrhage are common manifestations of SLE.

In most cases patients may also develop

nonspecific synovitis and

lymphocytic muscular infiltration.

Nonbacterial endocarditis is commonly seen, although its course is typically asymptomatic. Sometimes

verrucous endocarditis (Libman-Sacks endocarditis) associated with the involvement of mitral and tricuspid valves and resulting in valvular insufficiency is noted.

Pericarditis (serositis) and

myocarditis occur at higher rates in patients with SLE.

Table №1

Classification of lupus nephritis

| Types |

Characteristics |

Common clinical and laboratory findings |

| Type I (normal) |

No changes are detected by light microscopy, immunofluorescence stains or electron microscopy. |

None |

| Type II (mesangial) |

Type IIA. No changes are detected by light microscopy. However, immunofluorescence stains and electron microscopy demonstrate immunocomplex deposits in the mesangium. |

None |

| Type IIB. Light microscopy demonstrates immune deposits and/or sclerotic changes. |

Proteinuria < 1g/24h

Erythrocytes 5 – 15 in the field of vision |

| Type III (focal proliferative) |

Proliferation of peripheral capillary loops with segment distribution and involvement of less than 50 percent of glomerules and subendothelial immune deposits. |

Proteinuria < 2g/24h

Erythrocytes 5 – 15 in the field of vision |

| Type IV (diffuse proliferative) |

Proliferation of peripheral capillary loops with segment distribution and involvement of more than 50 percent of glomerules and subendothelial immune deposits. |

Proteinuria > 2g/24h

Erythrocytes > 20 in the field of vision

Presence of antigen

|

| Type V (membranous) |

Diffuse thickening of the basement membrane with epimembranous and intramembranous immune deposits without any necrotic changes. |

Proteinuria > 3,5g/24h

Hematuria is absent |

| Type VI (chronic glomerulosclerosis) |

Chronic sclerosis without any manifestations of inflammation and immune deposits. |

Presence of antigen

Renal failure |

Classification. Three treatment options are singled out depending on the onset of the disease, disease activity and its duration, extent of organ and system involvement and response to therapy. They are the following:

- Acute

- Subacute

- Chronic

In an

acute course of the disease SLE is characterised by a sudden onset, high fever, polyarthritis, serositis and lupus-specific skin rashes. Weight loss and fatigue can also be related to SLE. Within a few months patients with SLE may develop several clinical symptoms. Severe diffuse glomerulonephritis associated with progressive renal insufficiency can be a sign of active lupus.

In a

subacute course of the disease SLE is characterised by a gradual and intermittent onset. Skin involvement, arthralgia and arthritis, polyserositis, signs of nephritis and constitutional symptoms do not occur at the same time. Within a few years patients with SLE usually develop several clinical symtoms.

In a

chronic course of the disease SLE is characterised by relapses of certain clinical symptoms. Recurrent joint involvement is usually the earliest symptom. Arthralgia and polyarthritis represent the most common presenting complaints. Patients may also develop Raynaud’s syndrome, Verlgaulf’s syndrome, nervous system involvement (for example, epileptiform syndrome), kidney and skin involvement (for example, discoid lupus), and serous membrane involvement.

According to clinical and laboratory studies, 3 extents of disease activity are singled out.

Clinical manifestations. SLE may develop with the involvement of one organ system or it can affect many parts of the body. Its course is highly variable, with some experiencing a mild course with episodes of exacerbation of the disease and others an aggressive, rapidly progressive course. In most patients with SLE episodes of exacerbation of the disease are followed by periods of relative improvement. Complete remission occurs in about 20% of patients with SLE. It usually occurs after an exacerbation of the disease and treatment is not needed during this period.

Disease incidence is higher among women aged 20 – 30. Fatigue, weight loss, fever, skin rashes, nervous and mental disorders, myalgia and arthralgia are typically the earliest symptoms.

Sometimes the disease is clinically manifested by high fever, either subfebrile or remittent, septic, sudden weight loss, arthritis and lupus-specific skin rashes. Many parts of the body are typically involved in systemic lupus erythematosus.

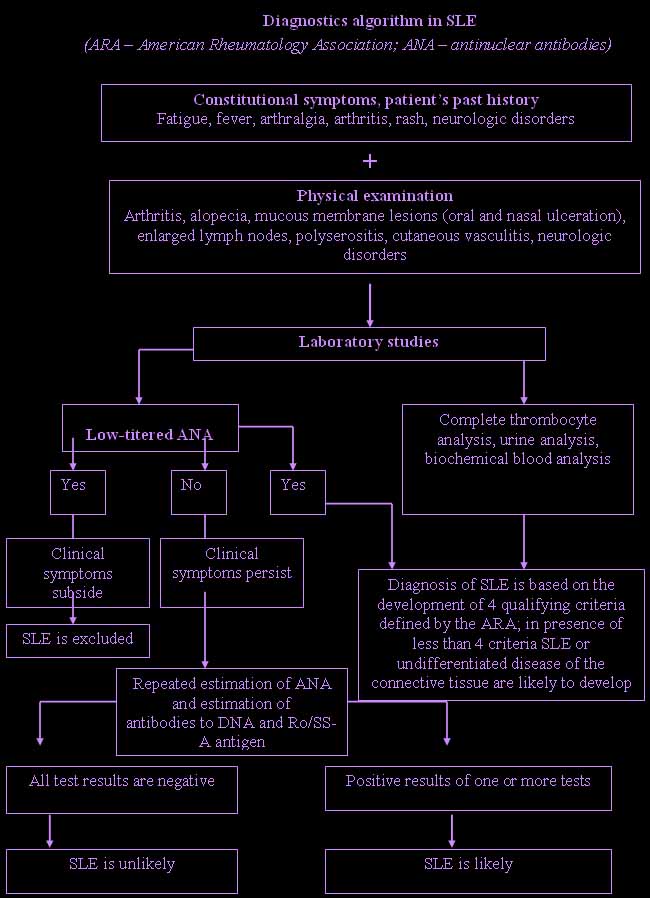

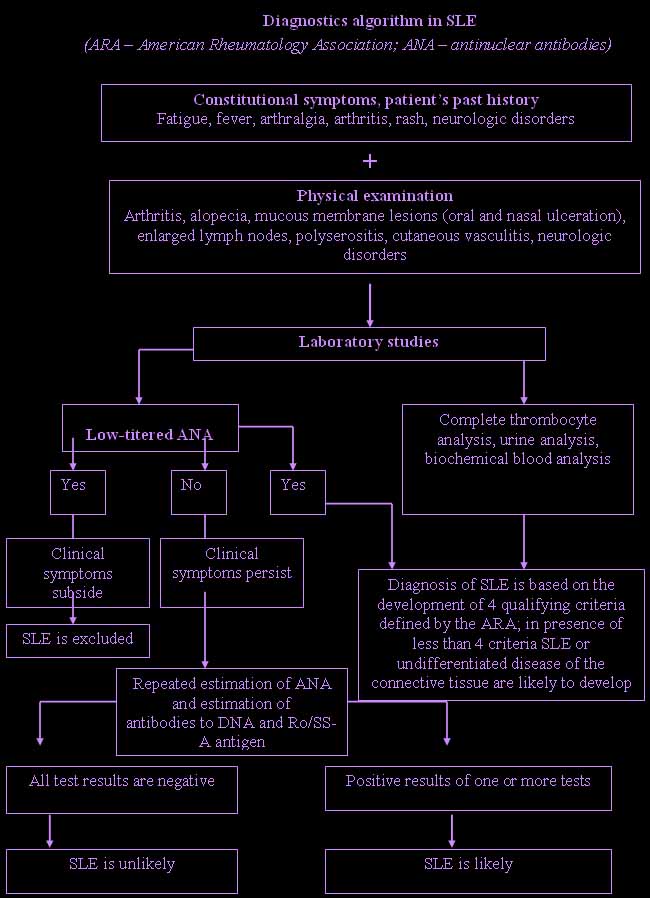

Diagnosis of SLE is somewhat difficult as it can be confused with some other rheumatic conditions.

Clinical syndromes.

Fever occurs in

25 percent of patients with SLE.

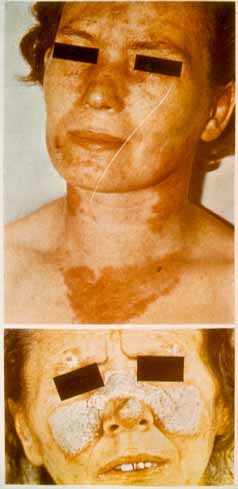

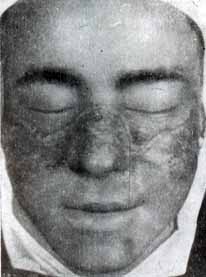

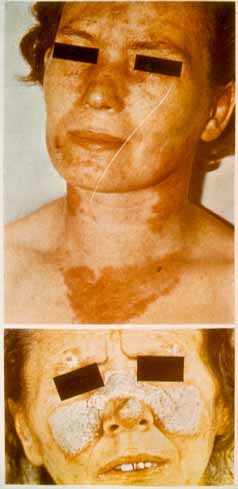

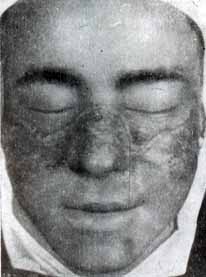

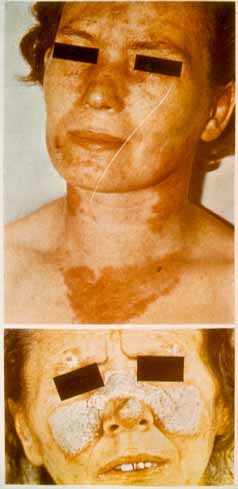

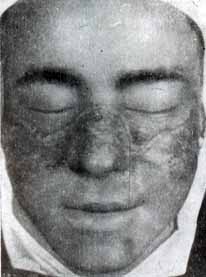

Skin and mucous membrane lesions. These include discoid loci with telangiectasias, “butterfly” rash developing as an erythematous lesion on the face, and especially in the area of the wings of the nose and malar area.

Cutaneous manifestations of SLE also include capillaritis of the tips of the fingers and alopecia. Sometimes cutaneous manifestations of SLE include bullous lesions, urticaria, erythema multiforme, panniculitis (lupus profundus).

Cutaneous vasculitis which is clinically manifested by hemorrhagic, papulonecrotic skin rashes, hyperpigmentation, infarction of nail walls and gangrene of fingers, also occur in patients with SLE. Sometimes patients with SLE may develop lupus-specific cheilitis. Lupus-specific cheilitis usually begins as edema and congestive hyperemia of the red border of the lips with compact, keratotic scaling, erosion and scarring atrophy.

Secondary Sjogren’s sicca syndrome

Secondary Sjogren’s sicca syndrome occurs in 25% of patients with SLE.

Every third patient develops Raynaud’s phenomenon. Livedo reticularis can be observed, especially in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

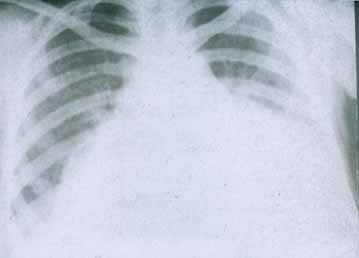

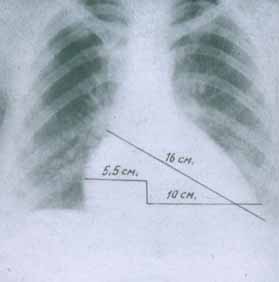

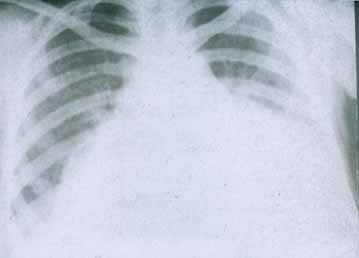

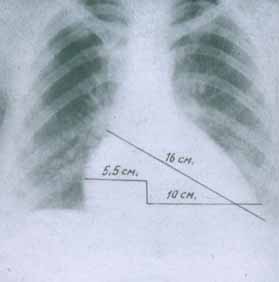

Serositis. Pleuritis, pericarditis, aseptic peritonitis without effusion into serous cavity occur in every second patient with SLE. In some cases serositis is associated with great pleural effusion complicated by cardiac tamponade, respiratory and heart failure.

C

ardiac involvement. Pericarditis is typically observed in 20 percent of patients with SLE.

Pericarditis accompanied by echocardiographic signs of pleural effusion presents in 50 percent of patients with SLE.

Myocarditis occurs very rarely.

Endocardium involvement usually results in aseptic Libman – Sacks endocarditis which is associated with thickening of the parietal endocardium in the area of the atrio-ventricular ring, less commonly – in the area of the mitral valve. Endocarditis is typically asymptomatic and is detected with the help of echocardiography. Libman – Sacks endocarditis is considered to be associated with the presence of antibodies to phospholipids. Endocarditis may be accompanied by embolism, valve dysfunction and infection.

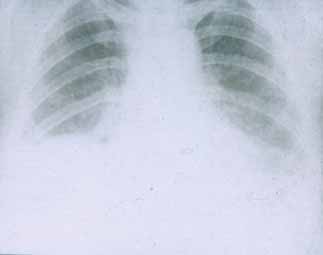

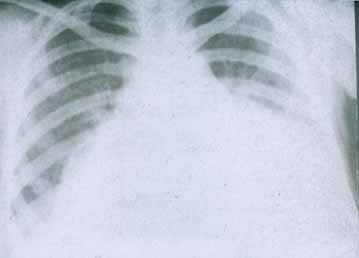

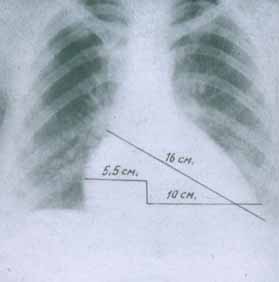

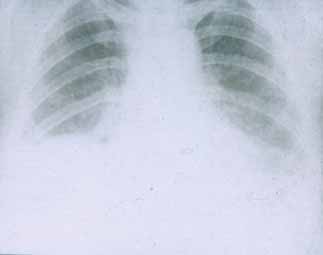

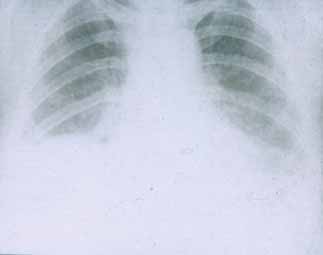

Pulmonary involvement. Pleurisy, either dry or exudative, more frequently bilateral, is observed in about 30 percent of patients with SLE.

Sometimes it is accompanied by pericarditis. Lupus pneumonitis should be distinguished from acute pneumonia. Lupus pneumonitis is often accompanied by fever, shortness of breath, cough and blood spitting (hemoptysis). Pleurisy is often associated with pleuritic chest pain, diminished respiration, moist rales in the lower part of the lungs. Diffuse interstitial lesions of the lungs occur quite rarely. Pulmonary hypertension resulting from recurrent embolism of pulmonary vessels occurs in active SLE patients rarely. Respiratory distress-syndrome occurring most commonly in adults and lung hemorrhage are acute pulmonary manifestations of SLE which are uncommon.

G

astrointestinal involvement. Nausea, impaired defecation and abdominal pain are frequent complaints in patients with active SLE. These symptoms can be due to lupus peritonitis. Lupus peritonitis can be complicated by vasculitis of mesenteric vessels which is associated with sharp, spasmodic (cramp-like) abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea.

Renal involvement. Most SLE patients demonstrate some degree of renal involvement. In patients with active SLE changes in urinary sediment accompanied by elevated creatinine and nitrogen blood levels are typically observed. Some other changes include reduced complement, presence of autoantibodies to native DNA and increased arterial blood pressure. Patients with great changes in urinary sediment, increased amount of antibodies to native DNA and reduced complement in the serum are at risk of getting severe glomerulonephritis. Presence of antibodies to DNA in blood serum and reduced complement usually indicate some degree of renal involvement.

According to a clinical classification suggested by I.E. Tareeva (1995), the following types of nephritis are singled out:

- Progressive or active lupus nephritis

- Nephritis associated with nephritic syndrome

- Nephritis associated with well pronounced urinary syndrome

- Nephritis associated with mild urinary syndrome and proteinuria.

Identification of the specific types of lupus nephritis aids in prognosis of the disease.

Mesangial nephritis is a relatively benign form of renal involvement. It is often asymptomatic. Immunosuppressive treatment is not needed in this case.

Focal proliferative nephritis is a less benign form of kidney involvement. It generally responds to treatment with immunosuppressive therapy.

Diffuse proliferative nephritis is severe renal involvement. It is often associated with arterial hypertension, various edematic syndromes, severe proteinuria, erythrocythuria and some clinical features of renal failure.

Membranous glomerulonephritis is associated with pronounced proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, hypocomplementemia, slight changes in urinary sediment and absence of arterial hypertension. Renal failure usually develops within the first few years after onset of the disease.

Reticuloendothelial system involvement: It is characterised by enlarged lymph nodes. It occurs in 30 – 70 percent of patients with SLE.

Cubital lymph nodes are involved more frequently. Along with this, spleen enlargement is a common manifestation of SLE.

Nervous system involvement. Central nervous system is frequently involved with highly varied presentation. All parts of the brain, meninges, the spinal cord, cranial and spinal nerves can be affected in SLE. Multiple lesions may also occur. In most cases, neurological involvement occurs in the context of other clinical and laboratory features of active SLE. A high percentage of patients with SLE have evidence of subtle cognitive impairment, headache of varying extent, more often migraine. Craniocerebral and ophthalmic nerve involvement may also occur. Patients may develop peripheral neuropathy either symmetric, sensory or motor, mononeuritis multiplex (less commonly), Hyenn-Barre’s syndrome (very rarely), stroke, transverse myelitis (rarely), chorea, acute psychosis, organic cerebral syndrome which is usually associated with emotional instability, episodes of depression, memory impairment, dementia, and seizures. Depression and anxiety disorders are common.

Musculoskeletal system involvement. Arthralgia and symmetric arthritis are common manifestations of presenting complaints in SLE. Arthritis is usually nondeforming. However, some patients may develop deformities called Jaccoud arthropathy which is due to ligament and tendon involvement rather than erosive arthritis. Joint involvement is usually associated with recurrent arthritis or arthralgia. The small joints of the hands, wrists, knees, and ankles are involved most frequently. Muscle involvement is often asymptomatic. However, inflammatory myopathy may occur.

Eye involvement. Choroiditis, episcleritis, conjunctivitis, ulcers of the cornea and xerophthalmia are common manifestations of SLE.

Lab studies. The ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) may be elevated but does not correlate with disease activity. Anemia is common and related mainly to chronic inflammation in episodes of exacerbation of the disease. Evidence of hemolytic anemia may be present, including jaundice, reticulocytosis and Coombs antibodies which are clinical manifestations of active SLE.

Complement levels (C3, C4) may be depressed in patients with active SLE.

Presence of hypergammaglobulinemia may reflect increased activity of B-lymphocytes.

High-titered antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and LE-cells are common in SLE. Antinuclear antibodies are not diagnostic of the disease, however, low-titered antinuclear antibodies may be present in blood serum, especially in the elderly. Antinuclear antibodies may be present in some other autoimmune disorders, viral infections, chronic inflammatory diseases. ANAs may be observed in patients with drug-induced lupus. Significance of other autoantibodies in SLE is shown in Table № 2.

Table № 2.

Autoantibodies in SLE

| Antibodies |

Detection rate, % |

Antigen |

Diagnostic value |

| Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) |

98 |

Various nuclear antigens |

ANA (antinuclear antibodies) screening test is more accurate when carried out on human cells rather than mice cells. SLE is unlikely when negative results are obtained in repeated ANA screening test.

|

| Antibodies to DNA |

70 |

Native DNA |

Antibodies to native DNA are more specific for SLE than antibodies to single-stranded DNA. |

| Antibodies to Sm-antigen |

30 |

Proteins bound with small nuclear RNA U1, U2, U4/6, U5 |

Common in SLE. |

| Antibodies to ribonucleoproteids |

40 |

Proteins bound with small nuclear RNA U1 |

High-titred antibodies to ribonucleoproteids are found in polymyositis, SLE, scleroderma systematica and combined disease of the connective tissue. Detection of antibodies to ribonucleoproteids without antibodies to DNA indicates low risk of glomerulonephritis. |

| Antibodies to Ro/SS-A antigen |

30 |

Proteins bound with RNA Y1-Y3 |

Antibodies to Ro/SS-A antigen are found in Sjögren’s sicca syndrome, subacute skin lupus, congenital complement insufficiency, SLE which is not accompanied by antinuclear antibodies, in the elderly with SLE, in lupus syndrome in newborns, congenital AV-blockade. May cause glomerulonephritis. |

| Antibodies to La/SS-B antigen |

10 |

Phosphoproteid |

Antibodies to Ro/SS-A antigen are always detected with antibodies to La/SS-B antigen. Detection of antibodies to La/SS-B antigen indicates low risk of glomerulonephritis. They are specific for Sjögren’s sicca syndrome. |

| Antibodies to DNA histones |

70 |

Histones |

They are common in patients with drug-induced lupus but are not specific for SLE. They are present in approximately 95% of patients. |

| Antiphospholipid antibodies |

50 |

Phospholipids |

Lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, different types of antiphospholipid antibodies can be detected by a number of different laboratory tests. Detection of lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies (especially high-titered IgG) indicates high risk of thrombosis, spontaneous abortion, thrombocytopenia and heart disease. |

| Antibodies to erythrocytes |

60 |

Erythrocytes |

Some patients with antibodies to erythrocytes in the serum may develop hemolytic anemia. |

| Antibodies to platelets |

30 |

Platelets |

Detected in thrombocytopenia. |

| Antibodies to lymphocytes |

70 |

Lymphocytes |

They cause leukopenia and dysfunction of T-lymphocytes. |

| Antibodies to neurons |

60 |

Membranes of neurons and lymphocytes |

According to a number of investigations, high-titred IgG antibodies to neurons are typical of SLE associated with diffuse central nervous system involvement. |

| Antibodies to P-protein of ribosome |

20 |

P-protein of ribosome |

According to a number of investigations, these antibodies are detected in SLE associated with depression and other mental disorders. |

Antiphospholipid syndrome occurs in 25 – 30 percent of patients with SLE. It is characterized by a triad of clinical manifestations. They include venous or arterial thrombosis, obstetrical pathology, such as antenatal fetal death, recurrent spontaneous abortions, and thrombocytopenia. These clinical manifestations are usually associated with increased production of antibodies to phospholipids (lupus anticoagulant, cardiolipin antibodies and/or false-positive Wassermann test). Isolated antibodies to phospholipids are found in 30 – 60 percent of patients with SLE.

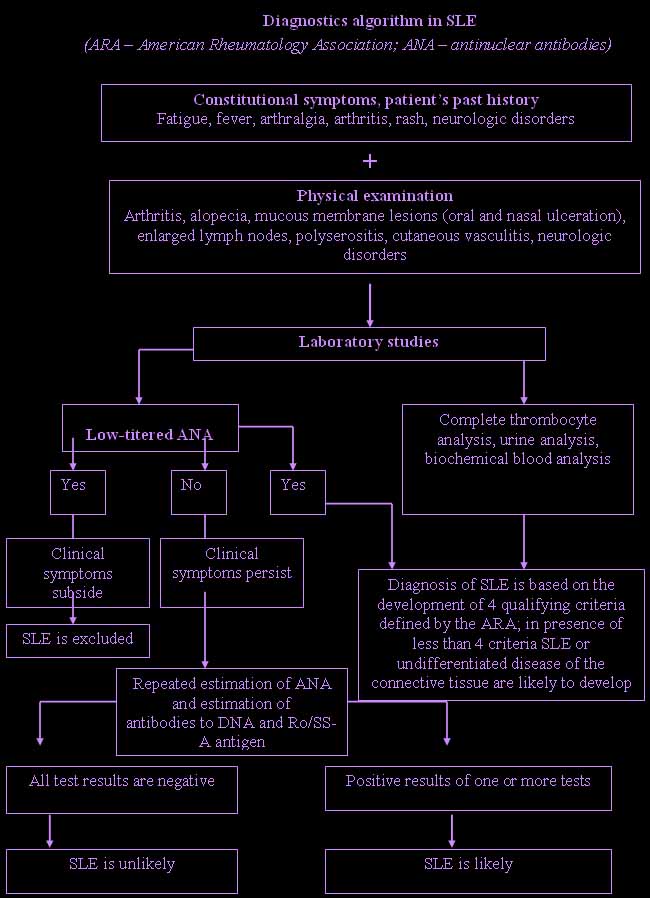

Diagnostics. In 1982 the American Rheumatology Association suggested classification criteria. Diagnosis is based on development of 4 out of 11 qualifying criteria. Nowadays these criteria are used in diagnostics.

Development of 4 criteria at any time period after the onset of the disease has been found to be 96% sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of SLE.

Classification criteria of SLE designed by the American Rheumatology Association

| 1. “Butterfly” rash, generalized erythema. |

Butterfly rash develops as a persistent erythematous lesion or plaques most often in a malar area. |

| 2. Discoid lupus erythematosus. |

Erythematous raised patches with keratotic scaling; follicular plugging mostly on scalp or face and scarring are common. |

| 3. Hypersensitivity to UV irradiation. |

Lupus-specific rashes in sun exposed areas. They are detected at physical examination or from patient’s past history. |

| 4. Mucous membrane lesions (oral and nasal ulceration) |

They are detected at physical examination. |

| 5. Arthritis. |

Without erosion of the articular surface, with ≥ joint involvement. It is characterised by swelling, tenderness and effusion. |

| 6. Serositis. |

Pleurisy or pericarditis (ECG changes, pericardial effusion or pericardium friction rub). |

| 7. Renal involvement. |

Proteinuria (> 0.5 g/day or clearly positive results of express test of urine for protein) or cylindruria (erythrocyte, granular, hyaline or mixed). |

| 8. Central nervous system involvement. |

Epileptic seizures or psychosis developing without an apparent cause. |

| 9. Hematologic abnormalities. |

Hemolytic anemia, leukopenia (below 4000), lymphopenia (below 1500) or thrombocytopenia (below 100 000) which are not drug-induced. |

| 10. Immunologic abnormalities. |

Antibodies to native DNA or Sm-antigen or antiphospholipid antibodies (cardiolipin antibodies, positive lupus anticoagulant or pseudopositive serologic reaction to syphilis within 6 months. |

| 11. Antinuclear antibodies. |

Stable high-titered antinuclear antibodies are detected by immunofluorescence or some other method excluding drug-induced lupus. |

Differential diagnostics.

Differential diagnostics. There are about 40 diseases which can be confused with SLE, especially in its earliest stages. The following problems should be considered:

- Rheumatoid polyarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Juvenile chronic arthritis

- Steele syndrome in adults

- Polymyositis

- Scleroderma systematica

- Combined disease of the connective tissue

- Idiopathic glomerulonephritis

- Fibromyalgia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Systemic vasculitis

- Drug-induced lupus (Hydralazine and procainamide, isoniazid, chlorpromazine, penicillaminum, methyldopha, chinidin, interferon-a,ethosuximidum have been strongly implicated in drug-induced lupus).

- SLE-specific skin lesions (discoid lupus, subacute skin lesions)

- Antiphospholipid syndrome (it can be secondary to SLE)

- Chronic active hepatitis

- Infectious diseases, such as borreliosis, tuberculosis, secondary syphilis, infectious mononucleosis, hepatitis B, HIV, ets.)

- Lymphoproliferative tumors

- Paraneoplastic syndromes

- Inflammatory bowel diseases.

Treatment of SLE. The most important objectives of treatment are the following:

1. Achieving induced remission which is not associated with any common manifestations of SLE.

2. Preventing episodes of exacerbation of the disease.

3. Maintaining a satisfactory condition between episodes of disease exacerbation.

Treatment of patients with SLE should be individualized.

Sunscreen lotions (with coefficient of protection more than 15 percent) containing para-aminobenzoic acid or benzophenons are useful for photoprotection of patients with SLE.

Steroid ointments are effective for cutaneous manifestations. They should be applied 2 – 3 times daily. Antimalarial preparations are useful to treat discoid lesions.

Systemic use of glucocorticoids (GC): Glucocorticoids are useful to treat severe clinical manifestations in exacerbation of the disease, generalization of the process, spreading of the disease to serous membranes, nervous system, heart, lungs, kidneys and other organs and systems.

The selection of a preparation and its dose depend on the severity of the disease, disease activity, and involved organs. The initial dose of glucocorticosteroids should be sufficient to decrease inflammation and suppress disease activity. Maximum dose of glucocorticosteroids is used until clinical symptoms of the disease become evident. Then the dose should be reduced to prevent a withdrawal syndrome.

“Pulse-therapy” foresees the use of IV (intravenous) therapy with high-dose methylprednisolone (500 – 1000 mg per day) for 3 – 5 days. High-dose methylprednisolone is usually used for severe disease activity. When the symptoms improve, repeated courses of “pulse-therapy” may be required every 3 – 4 weeks for 3 – 6 months.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Arthritis and arthralgia are common manifestations of SLE. In moderate extent of the disease activity NSAIDs are typically used to decrease joint inflammation. NSAIDs should be used very carefully because of possible side (adverse) effects. The use of selective COX-2 inhibitors requires further study.

Quinoline derivatives: Long-term use of chloroquine is recommended in chronic SLE associated with skin involvement. Dose should be 0,4 g per day for the first 3 – 4 months. Then the dose should be reduced to 0,2 g daily. Hydroxylochloroquine can also be used. Dose should be 0,25 – 0,5 g daily.

Antimalarial drugs are characterised by a hypolipidemic and antithrombotic action. Antimalarials do not usually have any side effects, such as retinopathy, skin rashes, myopathy, neuropathy.

Cyclophosphomide is usually used in “pulse-therapy”. Intravenous (IV) therapy with cyclophosphomide (10 – 15 mg/kg once every 4 weeks) is more beneficial as it causes hemorrhagic cystitis less commonly than oral administration of the drug.

Azathioprine (1 – 4 mg/kg daily) is administered to maintain remission of lupus nephritis induced by

cyclophosphomide. Azathioprine is usually used in autoimmune hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia which do not respond to glucocorticosteroid therapy.

Mophetil mycophenolate is a less toxic alternative to toxic cytostatic preparations in therapy and maintenance of lupus. The dose should be 1 – 3 g per day.

Cyclosporine A is usually administered in the dose of 2,5 – 3 mg daily. However, cyclosporine A should be limited as it increases the risk of renal side effects.

Cytotoxic preparations.

Indications for administration of cytotoxic drugs are the following:

- high extent of disease activity associated with involvement of various organs and systems, especially kidneys;

- proliferative and membranous lupus nephritis;

- unresponsiveness to treatment with high-dose glucocorticosteroids.

Anticoagulants and antiaggregants. They are used predominately in complex therapy of SLE. They also help in renal involvement, disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome (DIC), microcirculatory disturbances. Heparin acts as an anticoagulant. Doses of up to 10000 – 20000 activity units daily are typically used for some months. Persons with antiphospholipid syndrome should be administered high-dose warfarin to prevent arterial and venous thrombosis. The course of treatment with warfarin should be quite prolonged. The effectiveness of aspirin and heparin as prophylactic measures against arterial thrombosis has not been reported.

New approaches to treatment of SLE: Methods of apheresis, including plasmapheresis, lymphocytopheresis, cascade filtration of plasma and immunosorption, in combination with intravenous cyclophosphomide and glucocorticoids are being investigated now. Administration of intravenous immunoglobulin, as well as dehydroepiandrosterone, total irradiation of lymph nodes are also being studied now. Administration of substances which interfere with intracellular transmission of signal in activated T-lymphocytes and suppress production of cytokines contributing to inflammation and activating B-lymphocytes are considered as useful in treating SLE. These substances include thalidomide, bindarit, nucleoside analogs (for example, fludarabin and misorebin), leflunomide. Autologous transplantation of stem cells is also considered as a useful therapeutic measure.

Prevention of SLE. Prevention of SLE is secondary. It is aimed at prevention of exacerbation and progression of the disease.

Prognosis. Nowadays long-term prognosis of SLE is more favourable than it was 30 – 40 years ago. The decrease in mortality can be attributed to advancements in general medical care. The two-year survival rate now approaches 90-98 percent. The 5-year survival rate is 82-96 percent, 10-year survival rate – 50 percent, and 12-year survival rate is 63-75 percent.

In patients with active SLE autoantibodies develop only to 40 (although there are more than 2000) potentially autoantigenic cell components, the most important being DNA and intracellular nucleoprotein complexes (for example, nucleosome, ribonucleoproteins, Ro/La, etc.).

High immunogenicity of autoantigenic cell components is associated with their capability to cross-react and bind B-cell receptors and accumulate on cell surfaces. Various defects of cell immunity are common in SLE and are usually characterized by increased production of Th2-cytokines (IL-6, IL-4 and IL-10). The latter are considered to be autocrine factors of B-lymphocyte activation synthesizing antinuclear antibodies. However, estrogens are capable of stimulating synthesis of Th2-cytokines.

In patients with active SLE autoantibodies develop only to 40 (although there are more than 2000) potentially autoantigenic cell components, the most important being DNA and intracellular nucleoprotein complexes (for example, nucleosome, ribonucleoproteins, Ro/La, etc.).

High immunogenicity of autoantigenic cell components is associated with their capability to cross-react and bind B-cell receptors and accumulate on cell surfaces. Various defects of cell immunity are common in SLE and are usually characterized by increased production of Th2-cytokines (IL-6, IL-4 and IL-10). The latter are considered to be autocrine factors of B-lymphocyte activation synthesizing antinuclear antibodies. However, estrogens are capable of stimulating synthesis of Th2-cytokines.

Disturbances in the immune system occurring in SLE lead to the production of autoantibodies and immune complexes. T-lymphocytes also play an important role in the development of the disease. A high ratio of CD4 to CD8 T cells as well as some other T cells stimulate production of autoantibodies. Activation of autoreactive B- and T-lymphocytes in SLE is caused by many factors. They include defects in immune cell tolerance, apoptosis, production of anti-idiotypic antibodies, formation of immune complexes and proliferation of cells which control the immune response. These antibodies target cells leading to cell damage and their impaired function. Damaging action of some autoantibodies is accounted for by their link with some antigens, for example, with superficial erythrocyte or platelet antigens. Other autoantibodies can bind with several antigens. Antigen-antibody complexes can activate the complement leading to tissue involvement. Along with this, the presence of antibodies on cell membranes can lead to impaired functions of cells even when the complement is not activated.

Disturbances in the immune system occurring in SLE lead to the production of autoantibodies and immune complexes. T-lymphocytes also play an important role in the development of the disease. A high ratio of CD4 to CD8 T cells as well as some other T cells stimulate production of autoantibodies. Activation of autoreactive B- and T-lymphocytes in SLE is caused by many factors. They include defects in immune cell tolerance, apoptosis, production of anti-idiotypic antibodies, formation of immune complexes and proliferation of cells which control the immune response. These antibodies target cells leading to cell damage and their impaired function. Damaging action of some autoantibodies is accounted for by their link with some antigens, for example, with superficial erythrocyte or platelet antigens. Other autoantibodies can bind with several antigens. Antigen-antibody complexes can activate the complement leading to tissue involvement. Along with this, the presence of antibodies on cell membranes can lead to impaired functions of cells even when the complement is not activated.

Circulatory immune complexes and autoantibodies usually cause tissue involvement and impairement of functions of various organs. Skin, mucous membranes, central nervous system, kidneys and blood are most commonly involved in SLE.

Although pathogenesis of lupus nephritis is unknown, the following mechanisms are considered to be responsible for the onset of the disease: deposition of circulatory immune complexes; local formation of immune complexes; crossed interaction of antibodies to DNA with glomerule components.

Morphological changes. The most common microscopic changes are the following:

Circulatory immune complexes and autoantibodies usually cause tissue involvement and impairement of functions of various organs. Skin, mucous membranes, central nervous system, kidneys and blood are most commonly involved in SLE.

Although pathogenesis of lupus nephritis is unknown, the following mechanisms are considered to be responsible for the onset of the disease: deposition of circulatory immune complexes; local formation of immune complexes; crossed interaction of antibodies to DNA with glomerule components.

Morphological changes. The most common microscopic changes are the following:

Sometimes the disease is clinically manifested by high fever, either subfebrile or remittent, septic, sudden weight loss, arthritis and lupus-specific skin rashes. Many parts of the body are typically involved in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Sometimes the disease is clinically manifested by high fever, either subfebrile or remittent, septic, sudden weight loss, arthritis and lupus-specific skin rashes. Many parts of the body are typically involved in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Diagnosis of SLE is somewhat difficult as it can be confused with some other rheumatic conditions.

Clinical syndromes.

Fever occurs in 25 percent of patients with SLE.

Skin and mucous membrane lesions. These include discoid loci with telangiectasias, “butterfly” rash developing as an erythematous lesion on the face, and especially in the area of the wings of the nose and malar area.

Diagnosis of SLE is somewhat difficult as it can be confused with some other rheumatic conditions.

Clinical syndromes.

Fever occurs in 25 percent of patients with SLE.

Skin and mucous membrane lesions. These include discoid loci with telangiectasias, “butterfly” rash developing as an erythematous lesion on the face, and especially in the area of the wings of the nose and malar area.

Cutaneous manifestations of SLE also include capillaritis of the tips of the fingers and alopecia. Sometimes cutaneous manifestations of SLE include bullous lesions, urticaria, erythema multiforme, panniculitis (lupus profundus).

Cutaneous manifestations of SLE also include capillaritis of the tips of the fingers and alopecia. Sometimes cutaneous manifestations of SLE include bullous lesions, urticaria, erythema multiforme, panniculitis (lupus profundus).

Cutaneous vasculitis which is clinically manifested by hemorrhagic, papulonecrotic skin rashes, hyperpigmentation, infarction of nail walls and gangrene of fingers, also occur in patients with SLE. Sometimes patients with SLE may develop lupus-specific cheilitis. Lupus-specific cheilitis usually begins as edema and congestive hyperemia of the red border of the lips with compact, keratotic scaling, erosion and scarring atrophy.

Cutaneous vasculitis which is clinically manifested by hemorrhagic, papulonecrotic skin rashes, hyperpigmentation, infarction of nail walls and gangrene of fingers, also occur in patients with SLE. Sometimes patients with SLE may develop lupus-specific cheilitis. Lupus-specific cheilitis usually begins as edema and congestive hyperemia of the red border of the lips with compact, keratotic scaling, erosion and scarring atrophy.

Secondary Sjogren’s sicca syndrome occurs in 25% of patients with SLE. Every third patient develops Raynaud’s phenomenon. Livedo reticularis can be observed, especially in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Serositis. Pleuritis, pericarditis, aseptic peritonitis without effusion into serous cavity occur in every second patient with SLE. In some cases serositis is associated with great pleural effusion complicated by cardiac tamponade, respiratory and heart failure.

Cardiac involvement. Pericarditis is typically observed in 20 percent of patients with SLE.

Secondary Sjogren’s sicca syndrome occurs in 25% of patients with SLE. Every third patient develops Raynaud’s phenomenon. Livedo reticularis can be observed, especially in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Serositis. Pleuritis, pericarditis, aseptic peritonitis without effusion into serous cavity occur in every second patient with SLE. In some cases serositis is associated with great pleural effusion complicated by cardiac tamponade, respiratory and heart failure.

Cardiac involvement. Pericarditis is typically observed in 20 percent of patients with SLE.

Pericarditis accompanied by echocardiographic signs of pleural effusion presents in 50 percent of patients with SLE.

Myocarditis occurs very rarely.

Pericarditis accompanied by echocardiographic signs of pleural effusion presents in 50 percent of patients with SLE.

Myocarditis occurs very rarely.

Endocardium involvement usually results in aseptic Libman – Sacks endocarditis which is associated with thickening of the parietal endocardium in the area of the atrio-ventricular ring, less commonly – in the area of the mitral valve. Endocarditis is typically asymptomatic and is detected with the help of echocardiography. Libman – Sacks endocarditis is considered to be associated with the presence of antibodies to phospholipids. Endocarditis may be accompanied by embolism, valve dysfunction and infection.

Pulmonary involvement. Pleurisy, either dry or exudative, more frequently bilateral, is observed in about 30 percent of patients with SLE.

Endocardium involvement usually results in aseptic Libman – Sacks endocarditis which is associated with thickening of the parietal endocardium in the area of the atrio-ventricular ring, less commonly – in the area of the mitral valve. Endocarditis is typically asymptomatic and is detected with the help of echocardiography. Libman – Sacks endocarditis is considered to be associated with the presence of antibodies to phospholipids. Endocarditis may be accompanied by embolism, valve dysfunction and infection.

Pulmonary involvement. Pleurisy, either dry or exudative, more frequently bilateral, is observed in about 30 percent of patients with SLE.

Sometimes it is accompanied by pericarditis. Lupus pneumonitis should be distinguished from acute pneumonia. Lupus pneumonitis is often accompanied by fever, shortness of breath, cough and blood spitting (hemoptysis). Pleurisy is often associated with pleuritic chest pain, diminished respiration, moist rales in the lower part of the lungs. Diffuse interstitial lesions of the lungs occur quite rarely. Pulmonary hypertension resulting from recurrent embolism of pulmonary vessels occurs in active SLE patients rarely. Respiratory distress-syndrome occurring most commonly in adults and lung hemorrhage are acute pulmonary manifestations of SLE which are uncommon.

Gastrointestinal involvement. Nausea, impaired defecation and abdominal pain are frequent complaints in patients with active SLE. These symptoms can be due to lupus peritonitis. Lupus peritonitis can be complicated by vasculitis of mesenteric vessels which is associated with sharp, spasmodic (cramp-like) abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea.

Renal involvement. Most SLE patients demonstrate some degree of renal involvement. In patients with active SLE changes in urinary sediment accompanied by elevated creatinine and nitrogen blood levels are typically observed. Some other changes include reduced complement, presence of autoantibodies to native DNA and increased arterial blood pressure. Patients with great changes in urinary sediment, increased amount of antibodies to native DNA and reduced complement in the serum are at risk of getting severe glomerulonephritis. Presence of antibodies to DNA in blood serum and reduced complement usually indicate some degree of renal involvement.

According to a clinical classification suggested by I.E. Tareeva (1995), the following types of nephritis are singled out:

Sometimes it is accompanied by pericarditis. Lupus pneumonitis should be distinguished from acute pneumonia. Lupus pneumonitis is often accompanied by fever, shortness of breath, cough and blood spitting (hemoptysis). Pleurisy is often associated with pleuritic chest pain, diminished respiration, moist rales in the lower part of the lungs. Diffuse interstitial lesions of the lungs occur quite rarely. Pulmonary hypertension resulting from recurrent embolism of pulmonary vessels occurs in active SLE patients rarely. Respiratory distress-syndrome occurring most commonly in adults and lung hemorrhage are acute pulmonary manifestations of SLE which are uncommon.

Gastrointestinal involvement. Nausea, impaired defecation and abdominal pain are frequent complaints in patients with active SLE. These symptoms can be due to lupus peritonitis. Lupus peritonitis can be complicated by vasculitis of mesenteric vessels which is associated with sharp, spasmodic (cramp-like) abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea.

Renal involvement. Most SLE patients demonstrate some degree of renal involvement. In patients with active SLE changes in urinary sediment accompanied by elevated creatinine and nitrogen blood levels are typically observed. Some other changes include reduced complement, presence of autoantibodies to native DNA and increased arterial blood pressure. Patients with great changes in urinary sediment, increased amount of antibodies to native DNA and reduced complement in the serum are at risk of getting severe glomerulonephritis. Presence of antibodies to DNA in blood serum and reduced complement usually indicate some degree of renal involvement.

According to a clinical classification suggested by I.E. Tareeva (1995), the following types of nephritis are singled out:

Differential diagnostics. There are about 40 diseases which can be confused with SLE, especially in its earliest stages. The following problems should be considered:

Differential diagnostics. There are about 40 diseases which can be confused with SLE, especially in its earliest stages. The following problems should be considered:

In patients with active SLE autoantibodies develop only to 40 (although there are more than 2000) potentially autoantigenic cell components, the most important being DNA and intracellular nucleoprotein complexes (for example, nucleosome, ribonucleoproteins, Ro/La, etc.).

High immunogenicity of autoantigenic cell components is associated with their capability to cross-react and bind B-cell receptors and accumulate on cell surfaces. Various defects of cell immunity are common in SLE and are usually characterized by increased production of Th2-cytokines (IL-6, IL-4 and IL-10). The latter are considered to be autocrine factors of B-lymphocyte activation synthesizing antinuclear antibodies. However, estrogens are capable of stimulating synthesis of Th2-cytokines.

In patients with active SLE autoantibodies develop only to 40 (although there are more than 2000) potentially autoantigenic cell components, the most important being DNA and intracellular nucleoprotein complexes (for example, nucleosome, ribonucleoproteins, Ro/La, etc.).

High immunogenicity of autoantigenic cell components is associated with their capability to cross-react and bind B-cell receptors and accumulate on cell surfaces. Various defects of cell immunity are common in SLE and are usually characterized by increased production of Th2-cytokines (IL-6, IL-4 and IL-10). The latter are considered to be autocrine factors of B-lymphocyte activation synthesizing antinuclear antibodies. However, estrogens are capable of stimulating synthesis of Th2-cytokines.

Disturbances in the immune system occurring in SLE lead to the production of autoantibodies and immune complexes. T-lymphocytes also play an important role in the development of the disease. A high ratio of CD4 to CD8 T cells as well as some other T cells stimulate production of autoantibodies. Activation of autoreactive B- and T-lymphocytes in SLE is caused by many factors. They include defects in immune cell tolerance, apoptosis, production of anti-idiotypic antibodies, formation of immune complexes and proliferation of cells which control the immune response. These antibodies target cells leading to cell damage and their impaired function. Damaging action of some autoantibodies is accounted for by their link with some antigens, for example, with superficial erythrocyte or platelet antigens. Other autoantibodies can bind with several antigens. Antigen-antibody complexes can activate the complement leading to tissue involvement. Along with this, the presence of antibodies on cell membranes can lead to impaired functions of cells even when the complement is not activated.

Disturbances in the immune system occurring in SLE lead to the production of autoantibodies and immune complexes. T-lymphocytes also play an important role in the development of the disease. A high ratio of CD4 to CD8 T cells as well as some other T cells stimulate production of autoantibodies. Activation of autoreactive B- and T-lymphocytes in SLE is caused by many factors. They include defects in immune cell tolerance, apoptosis, production of anti-idiotypic antibodies, formation of immune complexes and proliferation of cells which control the immune response. These antibodies target cells leading to cell damage and their impaired function. Damaging action of some autoantibodies is accounted for by their link with some antigens, for example, with superficial erythrocyte or platelet antigens. Other autoantibodies can bind with several antigens. Antigen-antibody complexes can activate the complement leading to tissue involvement. Along with this, the presence of antibodies on cell membranes can lead to impaired functions of cells even when the complement is not activated.

Circulatory immune complexes and autoantibodies usually cause tissue involvement and impairement of functions of various organs. Skin, mucous membranes, central nervous system, kidneys and blood are most commonly involved in SLE.

Although pathogenesis of lupus nephritis is unknown, the following mechanisms are considered to be responsible for the onset of the disease: deposition of circulatory immune complexes; local formation of immune complexes; crossed interaction of antibodies to DNA with glomerule components.

Morphological changes. The most common microscopic changes are the following:

Circulatory immune complexes and autoantibodies usually cause tissue involvement and impairement of functions of various organs. Skin, mucous membranes, central nervous system, kidneys and blood are most commonly involved in SLE.

Although pathogenesis of lupus nephritis is unknown, the following mechanisms are considered to be responsible for the onset of the disease: deposition of circulatory immune complexes; local formation of immune complexes; crossed interaction of antibodies to DNA with glomerule components.

Morphological changes. The most common microscopic changes are the following:

Sometimes the disease is clinically manifested by high fever, either subfebrile or remittent, septic, sudden weight loss, arthritis and lupus-specific skin rashes. Many parts of the body are typically involved in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Sometimes the disease is clinically manifested by high fever, either subfebrile or remittent, septic, sudden weight loss, arthritis and lupus-specific skin rashes. Many parts of the body are typically involved in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Diagnosis of SLE is somewhat difficult as it can be confused with some other rheumatic conditions.

Clinical syndromes.

Fever occurs in 25 percent of patients with SLE.

Skin and mucous membrane lesions. These include discoid loci with telangiectasias, “butterfly” rash developing as an erythematous lesion on the face, and especially in the area of the wings of the nose and malar area.

Diagnosis of SLE is somewhat difficult as it can be confused with some other rheumatic conditions.

Clinical syndromes.

Fever occurs in 25 percent of patients with SLE.

Skin and mucous membrane lesions. These include discoid loci with telangiectasias, “butterfly” rash developing as an erythematous lesion on the face, and especially in the area of the wings of the nose and malar area.

Cutaneous manifestations of SLE also include capillaritis of the tips of the fingers and alopecia. Sometimes cutaneous manifestations of SLE include bullous lesions, urticaria, erythema multiforme, panniculitis (lupus profundus).

Cutaneous manifestations of SLE also include capillaritis of the tips of the fingers and alopecia. Sometimes cutaneous manifestations of SLE include bullous lesions, urticaria, erythema multiforme, panniculitis (lupus profundus).

Cutaneous vasculitis which is clinically manifested by hemorrhagic, papulonecrotic skin rashes, hyperpigmentation, infarction of nail walls and gangrene of fingers, also occur in patients with SLE. Sometimes patients with SLE may develop lupus-specific cheilitis. Lupus-specific cheilitis usually begins as edema and congestive hyperemia of the red border of the lips with compact, keratotic scaling, erosion and scarring atrophy.

Cutaneous vasculitis which is clinically manifested by hemorrhagic, papulonecrotic skin rashes, hyperpigmentation, infarction of nail walls and gangrene of fingers, also occur in patients with SLE. Sometimes patients with SLE may develop lupus-specific cheilitis. Lupus-specific cheilitis usually begins as edema and congestive hyperemia of the red border of the lips with compact, keratotic scaling, erosion and scarring atrophy.

Secondary Sjogren’s sicca syndrome occurs in 25% of patients with SLE. Every third patient develops Raynaud’s phenomenon. Livedo reticularis can be observed, especially in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Serositis. Pleuritis, pericarditis, aseptic peritonitis without effusion into serous cavity occur in every second patient with SLE. In some cases serositis is associated with great pleural effusion complicated by cardiac tamponade, respiratory and heart failure.

Cardiac involvement. Pericarditis is typically observed in 20 percent of patients with SLE.

Secondary Sjogren’s sicca syndrome occurs in 25% of patients with SLE. Every third patient develops Raynaud’s phenomenon. Livedo reticularis can be observed, especially in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Serositis. Pleuritis, pericarditis, aseptic peritonitis without effusion into serous cavity occur in every second patient with SLE. In some cases serositis is associated with great pleural effusion complicated by cardiac tamponade, respiratory and heart failure.

Cardiac involvement. Pericarditis is typically observed in 20 percent of patients with SLE.

Pericarditis accompanied by echocardiographic signs of pleural effusion presents in 50 percent of patients with SLE.

Myocarditis occurs very rarely.

Pericarditis accompanied by echocardiographic signs of pleural effusion presents in 50 percent of patients with SLE.

Myocarditis occurs very rarely.

Endocardium involvement usually results in aseptic Libman – Sacks endocarditis which is associated with thickening of the parietal endocardium in the area of the atrio-ventricular ring, less commonly – in the area of the mitral valve. Endocarditis is typically asymptomatic and is detected with the help of echocardiography. Libman – Sacks endocarditis is considered to be associated with the presence of antibodies to phospholipids. Endocarditis may be accompanied by embolism, valve dysfunction and infection.

Pulmonary involvement. Pleurisy, either dry or exudative, more frequently bilateral, is observed in about 30 percent of patients with SLE.

Endocardium involvement usually results in aseptic Libman – Sacks endocarditis which is associated with thickening of the parietal endocardium in the area of the atrio-ventricular ring, less commonly – in the area of the mitral valve. Endocarditis is typically asymptomatic and is detected with the help of echocardiography. Libman – Sacks endocarditis is considered to be associated with the presence of antibodies to phospholipids. Endocarditis may be accompanied by embolism, valve dysfunction and infection.

Pulmonary involvement. Pleurisy, either dry or exudative, more frequently bilateral, is observed in about 30 percent of patients with SLE.

Sometimes it is accompanied by pericarditis. Lupus pneumonitis should be distinguished from acute pneumonia. Lupus pneumonitis is often accompanied by fever, shortness of breath, cough and blood spitting (hemoptysis). Pleurisy is often associated with pleuritic chest pain, diminished respiration, moist rales in the lower part of the lungs. Diffuse interstitial lesions of the lungs occur quite rarely. Pulmonary hypertension resulting from recurrent embolism of pulmonary vessels occurs in active SLE patients rarely. Respiratory distress-syndrome occurring most commonly in adults and lung hemorrhage are acute pulmonary manifestations of SLE which are uncommon.

Gastrointestinal involvement. Nausea, impaired defecation and abdominal pain are frequent complaints in patients with active SLE. These symptoms can be due to lupus peritonitis. Lupus peritonitis can be complicated by vasculitis of mesenteric vessels which is associated with sharp, spasmodic (cramp-like) abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea.

Renal involvement. Most SLE patients demonstrate some degree of renal involvement. In patients with active SLE changes in urinary sediment accompanied by elevated creatinine and nitrogen blood levels are typically observed. Some other changes include reduced complement, presence of autoantibodies to native DNA and increased arterial blood pressure. Patients with great changes in urinary sediment, increased amount of antibodies to native DNA and reduced complement in the serum are at risk of getting severe glomerulonephritis. Presence of antibodies to DNA in blood serum and reduced complement usually indicate some degree of renal involvement.

According to a clinical classification suggested by I.E. Tareeva (1995), the following types of nephritis are singled out:

Sometimes it is accompanied by pericarditis. Lupus pneumonitis should be distinguished from acute pneumonia. Lupus pneumonitis is often accompanied by fever, shortness of breath, cough and blood spitting (hemoptysis). Pleurisy is often associated with pleuritic chest pain, diminished respiration, moist rales in the lower part of the lungs. Diffuse interstitial lesions of the lungs occur quite rarely. Pulmonary hypertension resulting from recurrent embolism of pulmonary vessels occurs in active SLE patients rarely. Respiratory distress-syndrome occurring most commonly in adults and lung hemorrhage are acute pulmonary manifestations of SLE which are uncommon.

Gastrointestinal involvement. Nausea, impaired defecation and abdominal pain are frequent complaints in patients with active SLE. These symptoms can be due to lupus peritonitis. Lupus peritonitis can be complicated by vasculitis of mesenteric vessels which is associated with sharp, spasmodic (cramp-like) abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea.

Renal involvement. Most SLE patients demonstrate some degree of renal involvement. In patients with active SLE changes in urinary sediment accompanied by elevated creatinine and nitrogen blood levels are typically observed. Some other changes include reduced complement, presence of autoantibodies to native DNA and increased arterial blood pressure. Patients with great changes in urinary sediment, increased amount of antibodies to native DNA and reduced complement in the serum are at risk of getting severe glomerulonephritis. Presence of antibodies to DNA in blood serum and reduced complement usually indicate some degree of renal involvement.

According to a clinical classification suggested by I.E. Tareeva (1995), the following types of nephritis are singled out:

Differential diagnostics. There are about 40 diseases which can be confused with SLE, especially in its earliest stages. The following problems should be considered:

Differential diagnostics. There are about 40 diseases which can be confused with SLE, especially in its earliest stages. The following problems should be considered: